1. Origins – Where It All Began

Maria: A Journey from the Fields to the Lecture Hall

Maria Sanchez grew up in a small agricultural town in California’s Central Valley. Her parents, both farmworkers who immigrated from Mexico, never had the opportunity to finish elementary school. From an early age, Maria translated documents, filled out government forms, and managed the family’s finances.

“I was nine when I filled out my first tax form,” she recalls with a soft chuckle. “My parents trusted me because I was the only one who could read and write in English.”

Maria’s road to college was filled with hurdles. No one in her family understood FAFSA, SATs, or college applications. Her high school counselor, however, saw her potential and helped guide her through the process.

“I remember crying when I got my acceptance letter from UCLA. I didn’t even know what it really meant to go to college, but I knew it was everything we had worked for.”

Jason: Navigating the Urban Labyrinth

Jason Brown grew up in South Side Chicago, raised by his grandmother after his mother passed away when he was ten. Education in his neighborhood wasn’t a top priority — survival was.

“College wasn’t a word we used. It wasn’t a goal; it was like talking about going to the moon.”

But Jason had a gift for storytelling and journalism. An English teacher took notice and introduced him to a summer journalism program at Northwestern University.

“That summer changed my life. I realized I had something to say, and people were willing to listen.”

With grit and support from mentors, Jason enrolled in Northwestern on a full scholarship. The transition was jarring. “I went from a school with metal detectors to classrooms with MacBooks. I was lost, but I wasn’t going to quit.”

2. The Hidden Curriculum – Learning What Others Already Know

First-gen students often arrive at college unaware of the “hidden curriculum” — unspoken rules and norms about how to succeed in academia. Office hours, networking, internships, and even how to email a professor professionally — these are not always intuitive.

Kimberly’s Story: Speaking Up

Kimberly Duong, the daughter of Vietnamese refugees, entered a prestigious liberal arts college on the East Coast. She was book-smart but socially unprepared.

“I thought I just needed to study hard and get good grades,” she says. “But then I learned that people were building relationships with professors, joining research labs, getting internships because they knew how to ask.”

She learned — slowly — that asking questions wasn’t a sign of weakness. It was a strategy for success. “I felt like everyone else had a manual, and I was just trying to figure it out as I went.”

Financial Literacy and Stress

Money is often a major barrier for first-gen students. Many work long hours or support their families while studying. This financial pressure can impact grades, mental health, and even retention rates.

“During finals, I was working 30 hours a week at a cafe,” says Jamal White, a first-gen student from Detroit. “I’d take my books into the break room and study during my shift. I was always tired, but I didn’t have another option.”

Despite financial aid, hidden costs like textbooks, lab fees, or transportation add up. And unlike their peers, first-gen students rarely have a financial safety net. One unexpected expense — a car breakdown or a medical bill — can derail their semester.

3. Impostor Syndrome – The Quiet Battle

Many first-gen students report feeling like impostors. Surrounded by peers who seem confident and worldly, they often question whether they belong.

“I kept thinking they made a mistake admitting me,” says Kimberly. “My roommates talked about their parents’ alma maters, vacations abroad, and I didn’t even own a suitcase.”

This psychological weight can be crushing. But it also builds resilience.

“Every day I stayed, I proved to myself that I belonged,” says Jason. “Eventually, I stopped apologizing for being different. I realized my story gave me something powerful — perspective.”

4. Family Ties – Bridging Two Worlds

Being the first in the family to attend college often creates a cultural chasm. First-gen students may feel torn between home and school, tradition and transformation.

The Weight of Expectation

Maria remembers the pride her parents felt. But also the loneliness. “They didn’t understand why I couldn’t come home every weekend. They’d say, ‘You’re getting an education, but don’t forget who you are.’ I never forgot. But I was changing, and that scared all of us.”

Jason had to educate his family as he educated himself. “I taught my grandmother what a bachelor’s degree was. She cried when she saw me in my cap and gown. Not because she understood what I did — but because she knew I had done something big.”

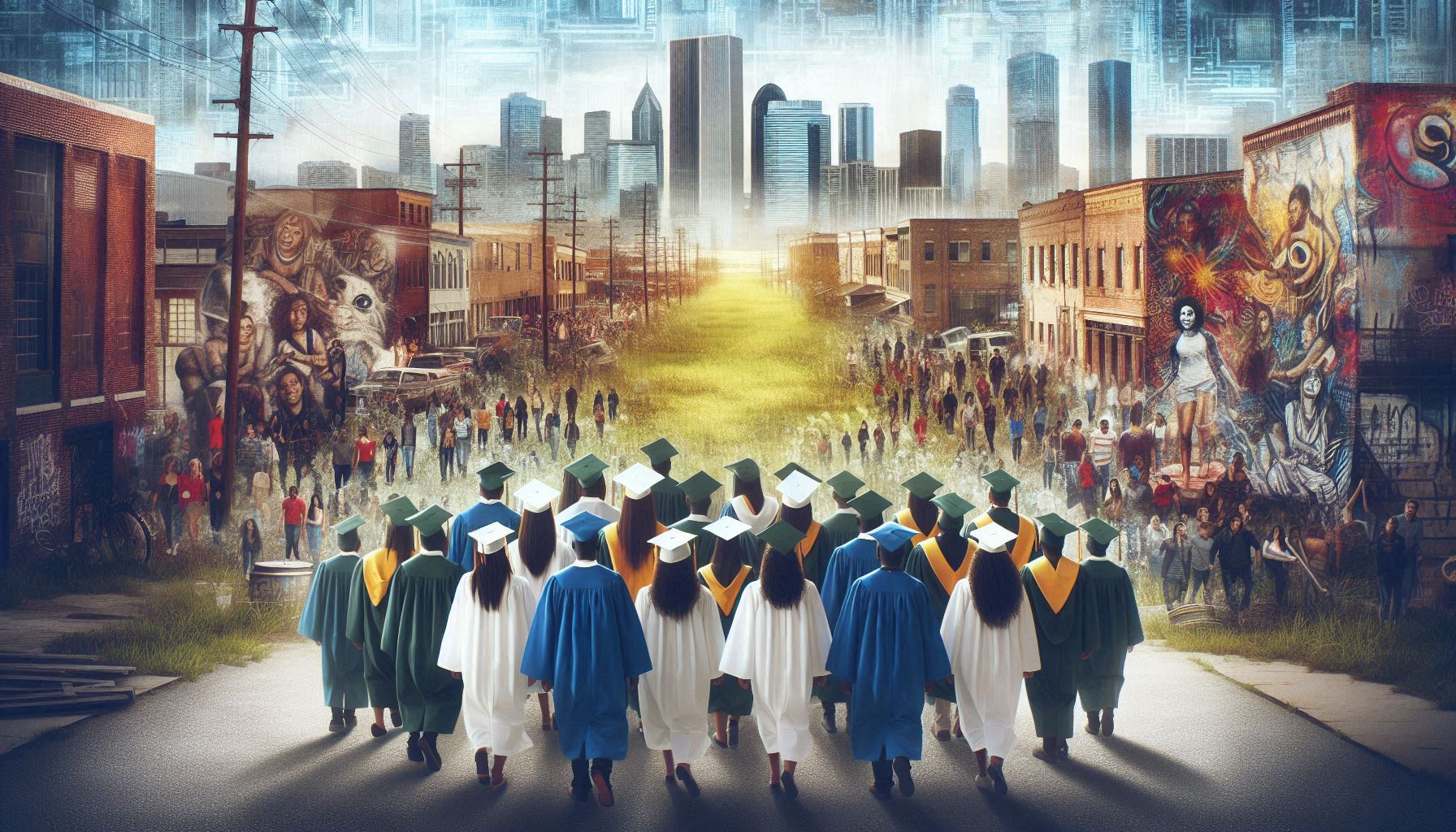

5. The Triumph – Graduation Day

Graduation is not just a personal milestone — it’s a communal victory. The images are iconic: families with handmade signs, grandparents crying, parents taking pictures with flip phones. These moments are filled with gratitude and the weight of generations.

Maria’s Cap Reads: ‘Para Mi Familia’

Maria’s graduation from UCLA was a full-circle moment. “I wore a sash with the Mexican flag. My cap said, ‘Para Mi Familia.’ My parents didn’t understand the ceremony, but they understood the moment.”

Jason’s grandmother wore her Sunday best and clapped louder than anyone. “She said, ‘Your mama would be proud.’ And I knew I had done it — for me, for her, and for the whole block.”

6. Beyond the Degree – What Comes Next

Graduating is only the beginning. First-gen graduates face new challenges: navigating the job market, pursuing graduate school, or becoming the support system for their families.

The Role of the Trailblazer

Many become mentors, guiding others through the path they once had to discover alone.

“I work at a nonprofit now that helps high schoolers apply to college,” says Kimberly. “I tell them all the things I wish someone had told me.”

7. Overcoming the Challenges of Academic Culture

The Learning Curve: Building Confidence in the Classroom

One of the most difficult transitions for first-generation students is adjusting to the academic culture of higher education. Many come from environments where formal education wasn’t always prioritized. For them, academic language, formal writing styles, and even classroom behavior — such as speaking up in class — can feel intimidating.

“I didn’t know how to take notes the way my peers did,” says Jonathan Ruiz, who graduated with a degree in political science from Columbia University. “I’d see people with fancy notebooks and color-coded pens, and I had a spiral notebook and a cheap pen from the 99-cent store. I felt so out of place. But I quickly realized that it wasn’t about the tools you had — it was about how you used them.”

Jonathan wasn’t the only one who struggled with this culture shock. First-generation students often face an academic “imposter syndrome,” where they feel as if they don’t have the same foundation of knowledge and skills that other students have, even though they’ve worked just as hard to get there. As he navigated through complex readings, assignments, and exams, Jonathan found that the key to success wasn’t simply following the rules but finding his own rhythm and voice.

“It took a long time, but I learned how to ask questions. I learned that it’s okay to not know everything right away. You’re here to learn, and nobody knows everything when they start. I stopped feeling embarrassed about asking for help. I started going to office hours, not just when I had problems, but to simply discuss ideas and build relationships.”

Jonathan’s experience highlights the importance of persistence and asking for help. Many first-generation students feel like they must do everything on their own, but over time, they learn that the key to succeeding in college is using available resources effectively. They build resilience by realizing they can, and should, seek support when necessary.

The Emotional and Psychological Toll of Being First-Gen

While the academic pressures of college can be overwhelming, the emotional and psychological strain that comes with being a first-generation student can be even more intense. These students often feel caught between two worlds: the world of higher education, where they may feel alienated, and the world of their families, where they may feel guilty for distancing themselves as they pursue their goals.

This emotional tug-of-war can result in heightened stress, anxiety, and depression. According to a 2020 report from the National Center for Education Statistics, first-generation students experience higher levels of anxiety and depression compared to their peers. Many feel an acute sense of responsibility to succeed — not just for themselves, but for their families, who sacrificed so much to provide them with the opportunity to attend college.

“I often felt like I was carrying the weight of my entire family on my shoulders,” says Alicia Gonzalez, a first-generation graduate in engineering. “I was the oldest, and my parents worked multiple jobs to support my education. I couldn’t fail. I couldn’t disappoint them. The pressure was crushing, and it was hard to talk about it because I didn’t want to seem ungrateful.”

The emotional isolation many first-generation students experience can sometimes make it harder to relate to others on campus. They may feel like they are the only ones dealing with these feelings. This is often compounded by the guilt that can arise from feeling like they have abandoned their roots or become too “academic” for their families.

Financial Strain: The Constant Balancing Act

The financial pressures of college are often more intense for first-generation students, who may not have the financial safety nets that others take for granted. Scholarships, financial aid, and work-study programs help, but many first-gen students still have to work part-time or even full-time jobs to make ends meet.

“I worked at a restaurant, a local bookstore, and a tutoring center, all while taking a full course load,” says Sophia Torres, a graduate in sociology from the University of Texas. “There were days when I wouldn’t sleep, just so I could make enough money to pay my rent and buy groceries. I barely had time to study, let alone relax or socialize. But I had no other choice.”

Sophia’s story is not unique. Many first-generation students experience what is known as “time poverty,” where they are so overburdened with work and school responsibilities that they have little to no time to engage in extracurricular activities or build social networks. This lack of connection can lead to feelings of isolation and burnout.

However, Sophia also reflects on the strength that came from these experiences. “The pressure was hard, but it made me stronger. It taught me how to manage my time and prioritize. And in the end, I realized that the hard work wasn’t just for me — it was for the generations to come. I had a bigger purpose.”

8. The Strain on Family Relationships

For many first-generation students, college is a transformative experience — but it can also put a strain on family relationships. When students leave home to attend college, they often feel disconnected from their families, who may not understand the demands of college life.

“I remember when I came home during my first winter break,” says Jonathan Ruiz. “My parents wanted me to stay home and help with the family business. They didn’t understand why I had to go back to school early to prepare for finals. I felt torn between two worlds — the world of my family, who needed me, and the world of my college, where I was building a future.”

This tension can also create a sense of guilt. Many first-generation students feel guilty for pursuing higher education, as it sometimes means distancing themselves from the values and expectations of their families. This is especially true for students who come from immigrant families, where the emphasis is often on survival, work, and community over individual academic achievement.

For students like Jonathan, the resolution often comes with time — and with the recognition that their success is, in fact, a collective success. “My parents didn’t understand the college experience, but they always supported me. They sacrificed everything so I could get this opportunity. Eventually, they saw how important it was, and they became my biggest cheerleaders.”

9. Mentorship and the Power of Community

One of the most important aspects of success for first-generation students is the presence of mentors and a supportive community. Many first-gen students find mentors in professors, campus advisors, or fellow students who have experienced similar struggles.

“Having someone who believes in you and who has been through the process themselves can make all the difference,” says Sophia Torres. “I was lucky to have a professor who mentored me. She didn’t just help me with my coursework — she helped me navigate the emotional and personal aspects of being a first-gen student. She became my sounding board and a source of strength.”

Mentorship is critical because it offers not only academic guidance but also emotional support. Many first-gen students struggle with self-doubt, feeling as though they don’t belong in college. Having someone who understands their journey can be incredibly validating and motivating.

In addition to formal mentorship, first-gen students often build their own networks of support with peers who share similar experiences. These peer groups provide a space where students can talk openly about the challenges they face, share advice, and uplift each other.

The First-Gen Movement: Empowerment Through Connection

There is also a growing movement of first-generation students who are uniting to create lasting change on college campuses. Student organizations, like First-Generation College Students groups, provide a safe space for students to express their struggles and successes while also advocating for resources and policy changes that address their needs.

“Joining the first-gen student organization was one of the best things I did,” says Alicia Gonzalez. “It gave me a sense of community. I realized that I wasn’t alone. We could share our stories, and together, we could advocate for more resources for first-gen students.”

These movements have not only helped first-gen students feel more empowered but have also influenced institutional policies, leading to more comprehensive support systems for first-generation students, such as mentorship programs, financial aid workshops, and mental health resources.

10. The Legacy – Building a Better Future for the Next Generation

For many first-generation graduates, the ultimate goal is to build a better future for their families and communities. Their accomplishments go beyond their own personal achievements; they are a legacy for future generations.

“I didn’t just go to college for myself,” says Jonathan. “I went for my family, for my community, and for all the other kids who think they can’t make it. I want them to know that it’s possible.”

As first-generation graduates enter the workforce, many choose to give back by mentoring others, creating opportunities in underserved communities, and advocating for policy changes. Their success represents a breaking of generational cycles, and their stories inspire countless others to follow in their footsteps.

“I know that because I went to college, my little brother and sister will know they can do it too,” says Maria. “The door is open now. And I’ll keep it open for the ones who come after me.”

Conclusion

First-generation graduates are rewriting the narrative of higher education. They are proving that success is not determined by family background, socioeconomic status, or race — but by determination, perseverance, and the willingness to push through obstacles. Their stories are a testament to the transformative power of education and the profound impact it has on individuals, families, and communities.

These graduates embody the resilience of the human spirit. They show that even when the odds are stacked against you, education can be the key to unlocking a better future. And, as more first-gen students graduate, they continue to pave the way for future generations to follow in their footsteps, creating a cycle of empowerment, hope, and opportunity.

SOURCES

American Council on Education. (2017). First-generation students: A snapshot of their challenges and opportunities. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Choy, S. P. (2001). Students whose parents did not go to college: Postsecondary access, persistence, and attainment. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Engle, J., & Tinto, V. 2008. Moving beyond access: College success for first-generation students. American Academic, 4(2), 1-16.

Gonzalez, J. M. 2014. The first-generation college student experience: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Higher Education, 85(1), 26-47.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2020). First-generation college students: College access, persistence, and postbaccalaureate outcomes. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. 2005. How college affects students: A third decade of research (Vol. 2). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Perkins, R., & Ditzfeld, C. 2018. The emotional labor of being a first-generation student in higher education: A qualitative analysis. Journal of College Student Development, 59(5), 551-565.

Rendon, L. I. 1994. Validating culturally diverse students: Toward a new model of learning and student development. In M. Lee (Ed.), Multiculturalism in higher education: The transformative role of diversity (pp. 27-39). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Terenzini, P. T., & Reason, R. D. 2005. Influences on student learning and development: An overview. In A. W. Chickering & Z. F. Gamson (Eds.), The seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education (pp. 1-14). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

HISTORY

Current Version

May 4, 2025

Written By

SUMMIYAH MAHMOOD