Introduction

In our modern world, stress is an almost constant companion. Whether it’s driven by work deadlines, financial concerns, family obligations, or even internal pressures, the body responds to stress in ways that were evolutionarily designed to keep us alive. However, while that response once served our ancestors well in life-or-death situations, it now wreaks havoc on the health of people under constant pressure. One of the most significant—yet often misunderstood—effects of stress is its relationship with weight gain, particularly around the waistline.

The key player in this biological drama? Cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. In this article, we will explore the role of cortisol in the stress response, examine how chronic stress can lead to weight gain (especially abdominal fat), and identify practical and science-backed strategies for stress and weight management.

What Is Cortisol?

Cortisol is a glucocorticoid hormone produced by the adrenal glands, located atop each kidney. It plays a vital role in numerous physiological functions, including:

- Regulating metabolism: It helps mobilize glucose (sugar), fats, and proteins to provide energy.

- Controlling blood sugar levels: Cortisol ensures an adequate energy supply during stress.

- Reducing inflammation: Cortisol has potent anti-inflammatory properties.

- Supporting memory and cognition: It helps in memory formation and focus.

- Maintaining blood pressure: Cortisol works with other hormones to keep cardiovascular function in check.

Cortisol production is governed by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. When the brain perceives a threat, the hypothalamus signals the pituitary gland to prompt the adrenal glands to release cortisol. This cascade prepares the body for a fight-or-flight response—heightened alertness, increased heart rate, elevated blood sugar levels—all designed to help deal with the threat.

Acute vs. Chronic Stress

Under acute stress (e.g., narrowly avoiding a car accident), cortisol spikes briefly and then returns to baseline. This is normal and healthy. The problem arises with chronic stress, where cortisol levels remain elevated over long periods, leading to negative consequences including:

- Fat accumulation (especially visceral fat)

- Impaired glucose tolerance

- Loss of muscle mass

- Increased appetite and food cravings

- Disrupted sleep

How Cortisol Affects Your Weight

- Increased Appetite and Food Cravings

Elevated cortisol affects the brain’s reward systems, making high-fat, high-sugar foods more appealing. It promotes the desire for “comfort foods” that trigger a dopamine release, giving short-term relief but long-term consequences. Research has shown that individuals under stress are more likely to eat calorie-dense, nutrient-poor foods.

In addition, cortisol interacts with ghrelin, the “hunger hormone,” to increase appetite. Ghrelin is secreted by the stomach when it’s empty, signaling hunger to the brain. Under stress, ghrelin levels increase, compounding the effects of cortisol and making it harder to resist unhealthy food choices.

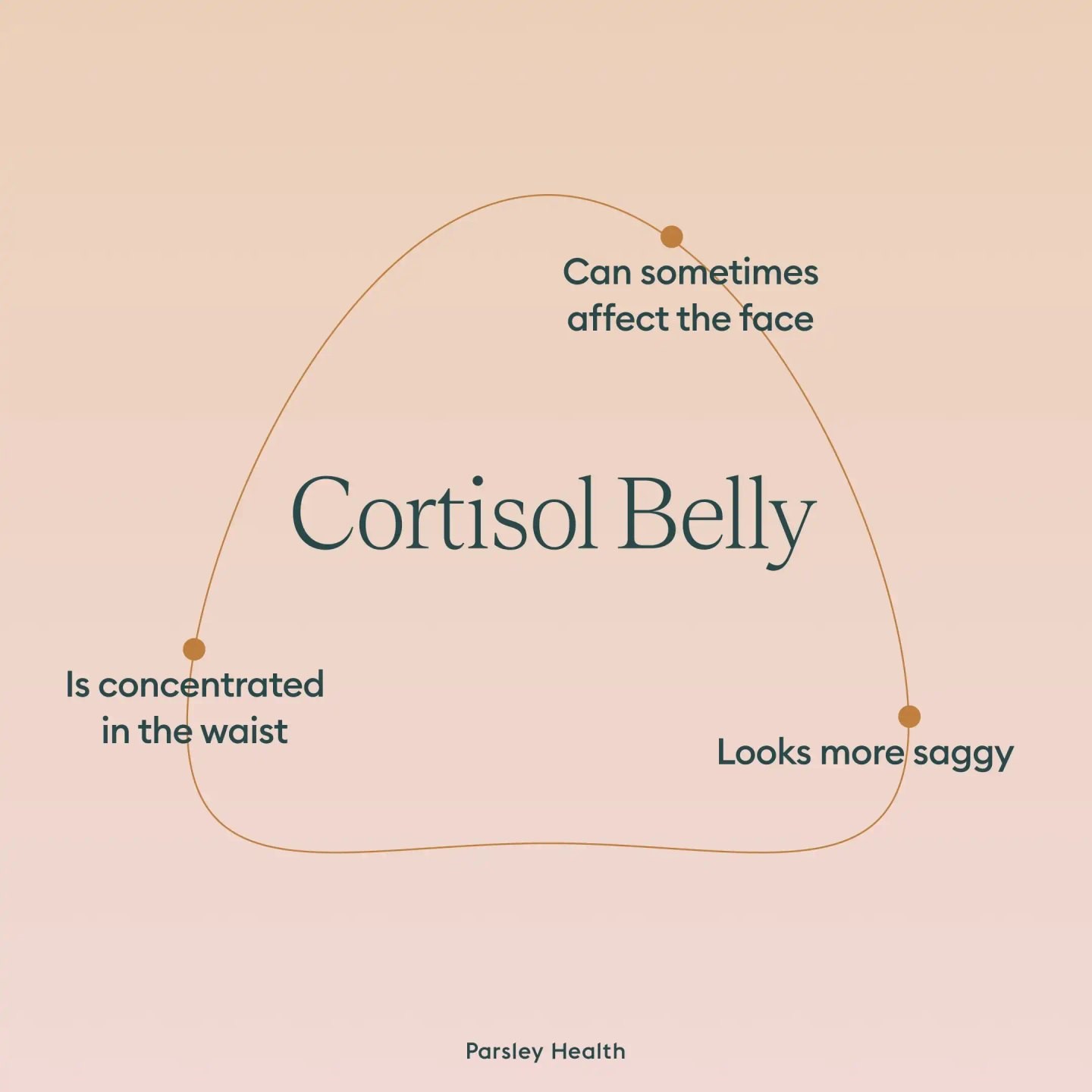

- Fat Storage and the “Stress Belly”

Cortisol doesn’t just increase your appetite; it also influences where fat is stored. High cortisol levels are strongly linked to visceral fat accumulation—fat that wraps around the abdominal organs. Unlike subcutaneous fat (which sits under the skin), visceral fat is metabolically active and dangerous. It produces inflammatory chemicals and hormones that contribute to:

- Insulin resistance

- High blood pressure

- Elevated triglycerides

- Increased risk for heart disease and type 2 diabetes

This central fat deposition is so commonly linked to stress and cortisol that it’s often called a “stress belly.”

- Insulin Resistance

Cortisol interferes with insulin sensitivity. Over time, chronically high cortisol causes the body’s cells to become resistant to insulin, meaning that more insulin is needed to keep blood sugar levels in check. This condition, known as insulin resistance, is a precursor to metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes—both of which are also associated with increased belly fat and difficulty losing weight.

- Muscle Wasting and Metabolic Slowdown

Cortisol not only increases fat storage—it also breaks down muscle tissue to release amino acids for energy. Muscle is metabolically active tissue, meaning it burns more calories at rest than fat does. When muscle mass decreases, basal metabolic rate (BMR) declines, making it easier to gain weight and harder to lose it.

The Psychological Link Between Stress and Eating

In addition to the biological impacts, chronic stress often leads to emotional eating—eating in response to feelings rather than hunger. Stress-related eating habits include:

- Mindless snacking while working or watching TV

- Binge eating episodes in response to acute stressors

- Skipping meals due to anxiety, followed by overeating later

- Craving sweets and carbs, which temporarily raise serotonin levels and improve mood

Over time, these behaviors form patterns that reinforce both stress and weight gain, creating a vicious cycle: stress leads to eating, which leads to guilt and more stress, and so on.

Stress, Sleep, and Weight Gain

Sleep and stress are intimately connected. Poor sleep is both a cause and consequence of elevated cortisol levels. Inadequate sleep leads to:

- Elevated evening cortisol levels

- Disruption of ghrelin and leptin (the satiety hormone)

- Decreased insulin sensitivity

- Increased appetite and cravings

Multiple studies have shown that people who consistently get fewer than 6 hours of sleep per night are more likely to have higher BMIs and more belly fat compared to those who sleep 7–9 hours.

Long-Term Health Risks of Cortisol-Induced Obesity

The weight gained from chronic stress isn’t just cosmetic—it’s dangerous. Long-term elevated cortisol and visceral fat accumulation are linked to numerous serious conditions:

- Cardiovascular disease: due to inflammation and dysregulated blood pressure

- Type 2 diabetes: due to insulin resistance and poor glycemic control

- Depression and anxiety: due to neurotransmitter imbalances

- Fatty liver disease

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in women

- Hormonal imbalances including reduced testosterone or estrogen

Strategies for Managing Cortisol and Reducing Stress-Related Weight Gain

Fortunately, there are proven, effective strategies to reduce cortisol levels, control appetite, and support weight loss:

Exercise—But Not Too Much

Moderate aerobic activity, strength training, yoga, and walking can all lower cortisol and improve insulin sensitivity. However, overtraining or extreme high-intensity exercise can increase cortisol, especially when combined with inadequate sleep or calories.

Ideal plan:

- 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week

- 2–3 sessions of strength training

- Yoga or stretching to reduce sympathetic nervous system dominance

Improve Sleep Hygiene

Good sleep is non-negotiable for managing cortisol. Sleep tips include:

- Maintain a consistent bedtime and wake time

- Limit caffeine after 2 p.m.

- Avoid screens at least 1 hour before bed

- Create a dark, cool, and quiet sleep environment

- Use relaxation techniques before bed (meditation, journaling)

Practice Mindfulness and Meditation

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programs have been shown to significantly lower cortisol levels. Techniques include:

- Breathwork: Deep diaphragmatic breathing

- Meditation: Guided, transcendental, or body scan

- Gratitude journaling

- Progressive muscle relaxation

Even 10–20 minutes daily can improve mental clarity, reduce anxiety, and improve eating behaviors.

Nutrition for Cortisol Balance

Foods that support cortisol regulation include:

- Complex carbs (oats, quinoa, legumes): support serotonin production

- Lean proteins: stabilize blood sugar

- Omega-3s: reduce inflammation (found in flax, chia, walnuts, fish oil)

- Magnesium-rich foods: leafy greens, seeds, and beans

- B-vitamins: whole grains, lentils, bananas (support adrenal health)

Avoid:

- Refined sugars

- Trans fats

- Excess caffeine

- Alcohol

Set Boundaries and Prioritize Self-Care

- Learn to say “no”

- Take breaks throughout the day

- Schedule downtime for hobbies and joy

- Use a planner to avoid overwhelm

Seek Professional Help When Needed

If chronic stress is affecting your health, relationships, or ability to function, seek support:

- Therapists specializing in CBT, DBT, or trauma

- Registered dietitians with experience in emotional eating

- Physicians to rule out underlying hormonal or metabolic conditions

Cortisol and Weight Gain

1. Increased Appetite and Cravings

Chronic stress and elevated cortisol levels can lead to increased appetite and cravings for high-calorie, sugary, and fatty foods. This is because cortisol can influence the brain’s reward system, making comfort foods more appealing during stressful times. Over time, this can lead to overeating and weight gain.

2. Fat Storage in the Abdominal Area

Cortisol has been shown to promote fat storage in the abdominal area, leading to what is commonly referred to as “stress belly.” Visceral fat, the fat stored around internal organs, is particularly concerning as it is associated with an increased risk of various health problems, including heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers.

3. Insulin Resistance

Chronic stress and elevated cortisol levels can lead to insulin resistance, a condition where the body’s cells become less responsive to insulin. This can result in higher blood sugar levels and increased fat storage, particularly in the abdominal area. Insulin resistance is also a risk factor for developing type 2 diabetes.

4. Muscle Breakdown

Prolonged elevated cortisol levels can lead to muscle breakdown. Since muscle tissue burns more calories than fat tissue, a decrease in muscle mass can slow down metabolism, making it easier to gain weight and harder to lose it.

Stress-Induced Eating Behaviors

Stress can also lead to unhealthy eating behaviors, such as emotional eating or stress eating. These behaviors involve consuming food in response to emotions rather than hunger, often leading to the consumption of high-calorie comfort foods. Over time, these eating patterns can contribute to weight gain and other health issues.

Managing Stress to Control Weight

Managing stress effectively is crucial for controlling cortisol levels and maintaining a healthy weight. Here are several strategies that can help:

1. Regular Physical Activity

Engaging in regular physical activity is one of the most effective ways to reduce stress and lower cortisol levels. Exercise helps the body use up excess energy and produces endorphins, chemicals in the brain that act as natural painkillers and mood elevators. Activities such as walking, jogging, yoga, and strength training can help manage stress and support weight loss efforts.

2. Adequate Sleep

Getting enough quality sleep is essential for stress management and weight control. Lack of sleep can increase cortisol levels and appetite, leading to weight gain. Aim for 7–9 hours of sleep per night and establish a regular sleep routine to improve sleep quality.

3. Mindfulness and Relaxation Techniques

Practicing mindfulness and relaxation techniques can help reduce stress and lower cortisol levels. Techniques such as meditation, deep breathing exercises, and progressive muscle relaxation can promote relaxation and improve emotional well-being.

4. Balanced Diet

Eating a balanced diet rich in whole foods, including fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains, can help regulate cortisol levels and support overall health. Avoiding excessive consumption of caffeine, alcohol, and high-sugar foods can also help manage stress and prevent weight gain.

5. Social Support

Building and maintaining strong social connections can help buffer against stress and its effects on the body. Spending time with friends and family, engaging in social activities, and seeking support when needed can improve resilience to stress and promote overall well-being.

6. Professional Help

If stress becomes overwhelming and difficult to manage, seeking professional help from a healthcare provider or mental health professional can be beneficial. Therapy, counseling, and stress management programs can provide tools and strategies to cope with stress effectively.

Conclusion

Stress may be an unavoidable part of life, but its effects on your waistline don’t have to be inevitable. Chronic stress, when unmanaged, triggers elevated cortisol levels that alter metabolism, increase appetite, and encourage fat storage—especially around the midsection. But the story doesn’t end there.

By understanding how cortisol works and implementing lifestyle changes—improving sleep, exercising wisely, eating a balanced diet, practicing mindfulness, and seeking support—you can reduce your cortisol levels and regain control over your health and weight. The body is remarkably resilient when given the right tools to heal.

SOURCES

Adam, T. C., & Epel, E. S. (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior, 91(4), 449–458.

Björntorp, P. (2001). Do stress reactions cause abdominal obesity and comorbidities? Obesity Reviews, 2(2), 73–86.

Brunner, E. J., Chandola, T., & Marmot, M. G. (2007). Prospective effect of job strain on general and central obesity in the Whitehall II Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 165(7), 828–837.

Chrousos, G. P. (2009). Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 5(7), 374–381.

Dallman, M. F., Pecoraro, N. C., & la Fleur, S. E. (2005). Chronic stress and comfort foods: Self-medication and abdominal obesity. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 19(4), 275–280.

Epel, E. S., McEwen, B. S., Seeman, T., Matthews, K., Castellazzo, G., Brownell, K. D., Bell, J., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Stress and body shape: Stress-induced cortisol secretion is consistently greater among women with central fat. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(5), 623–632.

Foley, P., & Kirschbaum, C. (2010). Human hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis responses to acute psychosocial stress in laboratory settings. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(1), 91–96.

Lupien, S. J., McEwen, B. S., Gunnar, M. R., & Heim, C. (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434–445.

Maniam, J., & Morris, M. J. (2012). The link between stress and feeding behaviour. Neuropharmacology, 63(1), 97–110.

McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873–904.

Porth, C. M., & Matfin, G. (2009). Pathophysiology: Concepts of altered health states (8th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers: The acclaimed guide to stress, stress-related diseases, and coping (3rd ed.). Henry Holt and Company.

Sinha, R., & Jastreboff, A. M. (2013). Stress as a common risk factor for obesity and addiction. Biological Psychiatry, 73(9), 827–835.

Whitworth, J. A., Williamson, P. M., Mangos, G., & Kelly, J. J. (2005). Cardiovascular consequences of cortisol excess. Vascular Health and Risk Management, 1(4), 291–299.

HISTORY

Current Version

May, 02, 2025

Written By

BARIRA MEHMOOD